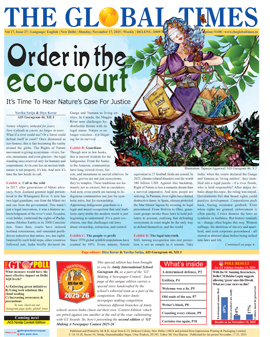

Order in the eco-court

It’s Time To Hear Nature’s Case For Justice

Yuvika Satija & Diya Kerur

AIS Gurugram 46, XII J

Nature whispers, unheard for years,

Now it pleads in courts, no longer in tears.

What if a river could sue? Or a forest could defend itself in court? Once dismissed as eco-fantasy, this is fast becoming the reality around the globe. The Rights of Nature movement is giving ecosystems - rivers, forests, mountains, and even glaciers - the legal standing once reserved only for humans and corporations. At its core lies an ancient truth: nature is not property, it’s kin. And now it’s time the law heeds its call.

Exhibit A: Call to the wild

In 2017, after generations of Māori advocacy, New Zealand granted legal personhood to the Whanganui River. It now has two legal guardians, one from the Māori iwi and one from the government. This wasn’t just a legal innovation, it was a historic acknowledgment of the river’s soul. Ecuador, even bolder, enshrined the rights of Pachamama (Mother Earth) in its 2008 Constitution. Since then, courts have ordered wetland restorations, and reminded profit-driven industries that nature, too, has rights. Inspired by such bold steps, other countries followed suit. India briefly declared the Ganga and Yamuna as living entities. In Canada, the Magpie River now challenges hydroelectric threats with its legal status. Nature is no longer voiceless - it is litigating for its survival.

Exhibit B: Guardians

Though new in law books, this is ancient wisdom for the Indigenous. From the Andes to the Amazon, communities have long viewed rivers, forests, and mountains as sacred relatives. In India, groves are not just ecosystems, they’re temples. These traditions see humanity not as owners, but as caretakers. And now, even courts are turning to Indigenous communities not just for symbolic roles, but for stewardship. Appointing Indigenous guardians is a legal and moral recognition that oral traditions carry truths the modern world is just beginning to understand. It’s a quiet revolution, one that challenges old laws about ownership, extraction, and control.

Exhibit C: The people vs profit

Since 1970 global wildlife populations have crashed by 69%. Every minute, forests equivalent to 27 football fields are erased. In 2023, climate-related disasters cost the world 380 billion USD. Against this backdrop, Right of Nature is less a romantic dream than a survival imperative. And now, people are noticing. In Panama, river rights have stalled destructive dams; in Spain, citizens protected the Mar Menor lagoon by securing its legal personhood. From Bolivia to Ohio, grassroots groups invoke these laws to hold polluters to account, realizing that defending ecosystems in court might be the only way to defend themselves, and the world.

Exhibit D: The legal labyrinth

Still, turning recognition into real protection is not as simple as it sounds. Take India: when the courts declared the Ganga and Yamuna as ‘living entities’, they stumbled into a legal puzzle - if a river floods, who is held responsible? After major debates about this topic, the ruling was stayed. Governments fret that broad rights could paralyse development. Corporations push back, fearing economic gridlock. Even when rights are granted, enforcement is often patchy. Critics dismiss the laws as symbolic or toothless. But history reminds us - change often begins this way. Women suffrage, the abolition of slavery and apartheid, and even corporate personhood - all started as abstract ideas before being etched into laws and life.

Continued on page 4...